‘Science that leads to action’: BRN project aims to improve diabetes care for racialized communities in the GTA

In Canada, 14 per cent of the population live with diabetes. That number is expected to increase to 27 per cent by 2032. Type 2 diabetes represents more than 90 per cent of all diabetes cases. Over one third of people living with Type 2 diabetes don’t know they have it and remain undiagnosed.

While the health condition disproportionally affects South Asian, Black and Indigenous populations in Canada – who are at higher risk of Type 2 diabetes – screening is vital to early detection of the disease and preventing devastating complications such as blindness and amputations.

New research led by Dr. Azza Eissa, a clinician scholar research fellow at the University of Toronto’s department of family and community medicine and a trainee in the Clinician Investigator Program, will explore disparities in diabetes screening for Black patients in Toronto utilizing self-reported health equity survey data linked to electronic medical records.

The work is supported by the Canadian Institute of Health Research and the Black Research Network’s IGNITE grant.

“Traditionally, research on racial disparities focuses on individual patient factors,” Eissa says. “For this research, we wanted to focus on the practice level factors and provider quality of care by looking at patients with inadequate screening for diabetes.”

To identify if there is a common trend in inadequate diabetes screening for Black, South Asian and white patients, Eissa will analyze health equity data collected by the St Michael’s Hospital Academic Family Health Team (SMHAFHT). She will compare results from 2019 and 2022 – pre- and post-pandemic – to further understand the quality of care given to racialized patients.

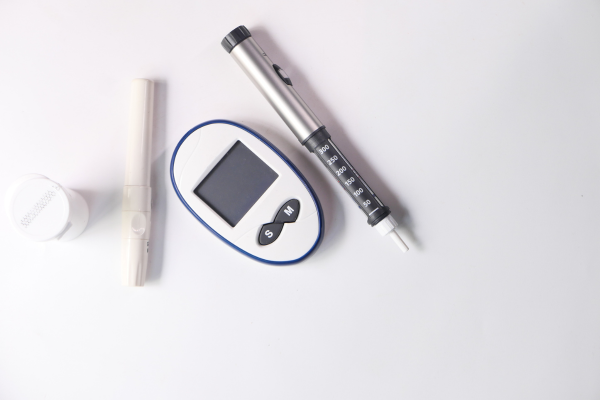

Trends in the data from the SMHAFHT will help Eissa determine if there is an association between self-reported race and inadequate screening. Inadequate screening is measured by quantifying patients who are eligible for screening as per guidelines but have not had a fasting blood glucose or HbA1c – a blood test that measures the average blood sugar levels over a three-month period – in the past three years.

Race and ethnicity are amongst the top factors in one’s risk to develop diabetes. Yet, inequities in the social determinants of health including providers’ unconscious bias and structural racism are prevalent barriers for racialized communities to access proper care.

Guidelines recommend that patients who are 40 years of age and above must be screened for diabetes once every two to three years. If patients have risk factors for diabetes, screening should start at the age of 35 or even earlier.

“It is hard to quantify the prevalence of inadequate screening. Part of what many family physicians try to do is use quality improvement efforts to provide equitable and high-quality care,” Eissa says.

“We are trying to ensure timely screening for patients to prevent complications for those at risk. Right now, we don’t know if there is a delay in diagnosis for racialized patients.”

The team will also examine other systemic and patient factors that are likely to be associated with differential diabetes screenings, such as patient’s income, housing, immigration status, body mass index, blood pressure, cholesterol levels, medications and number of clinical visits. In addition, Eissa will note factors such as who examined the patient – whether they were seen by a physician, nurse or resident. They plan to have a statistical analysis done in the next six months.

Eissa explains that a big gap in health equity research is the lack of community engagement in interpreting data on diabetes inequities and when determining best solutions in primary care. Once data is collected, she will work with an advisory board of Black physicians and community members to discuss meaningful solutions.

Some of the partners she will work with include the Black Creek Health Centre, TAIBU Health Centre, Diabetes Canada, the Black Health Alliance and the Black Physicians Association of Ontario. With the help of the IGNITE grant, a medical student – of an equity-deserving group who is interested in the social determinants of health – has joined the team for the summer.

Eissa hopes to share findings from the project with the Black Research Network, the University of Toronto Clinician Investigator Program Annual Symposium and the North American Primary Care Research Group in the fall.

“The goal is not just a scientific inquiry, it’s science that leads to action and science that is meaningful in terms of tangible changes to the impacted community.”

“We hope that this research will lead to more community involvement in science and help in changing some of the misunderstandings and mistrust racialized communities have when it comes to clinical research and medical science.”